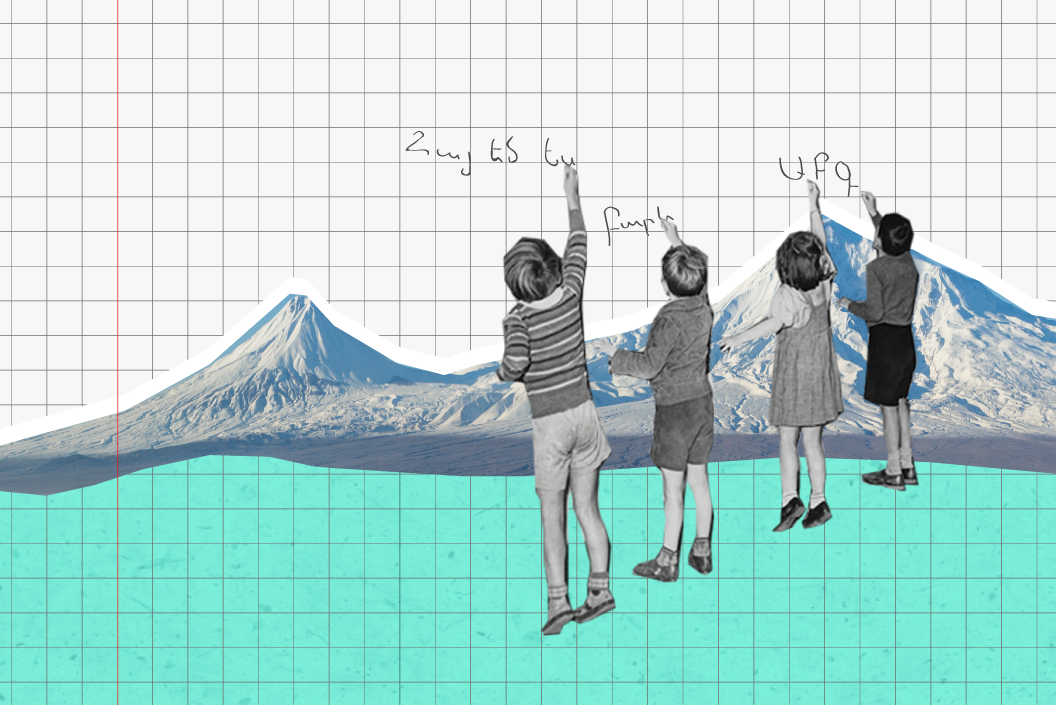

Revisiting Culture, Education and Statehood

Posted on March. 28. 2021

BY VAHAN ZANOYAN

In November 2019, when a bitter political controversy about education and culture was brewing in Yerevan, I published an article in Armenian, entitled “Culture, Education, Statehood, Citizenship.” That was 10 months before the outbreak of the Artsakh War and more than a year before its devastating end. Armenia was a different place then, and, in spite of the acrimonious debate that had erupted around the “Super Ministry” of Education, Science, Culture and Sports, the country was a much happier place than today. Today, as the nation struggles to come to grips with the catastrophic defeat, discussing matters of culture and education seems like a frivolous luxury.

But the topic is even more relevant now than it was back then. One of the points of that article was that despite our otherwise very rich cultural heritage, fate has deprived the Armenian nation of a culture of statehood. That means, we have not had the opportunity to develop a tradition of sovereignty, citizenship, governance, security, operational patriotism (versus emotional patriotism, of which we have plenty). Armenians have been citizens of many countries, but only very briefly citizens of Armenia. In the past 646 years, there’s been an independent and sovereign Armenian state for only 32 years, divided between the first and third republics; and another 71 years of non-sovereign statehood, during the second republic, when the Armenian SSR was part of the USSR. The rest of the time, even non-Diaspora Armenians lived as subjects of various foreign empires—Russian, Ottoman, Persian.

The problem, and the point of this argument, is that as subjects of foreign empires, a significant portion of the Armenian population has been conditioned to accommodate the ruling authority in order to survive; it has learned to “trade” independence and sovereignty for economic and physical survival. Beyond that, Armenians have managed to salvage an important cultural heritage. But, as a nation, we have not had the opportunity to focus on our own military security or state sovereignty. This was equally true for Armenian subjects of the Ottoman empire, the Russian empire and for citizens of the Soviet Union, even though as part of the Soviet Union, Armenia was not just an ethnic community within an empire, but a separate republic, with distinct borders, a local government and governmental institutions, and with a strong nationalistic culture and considerable autonomy when it came to preserving its cultural identity and practicing local governance. The economic, scientific and cultural achievements of the Armenian population were remarkable in this period, often in spite of the oppressive hand of the central authorities of the USSR. But the Armenian SSR was not a sovereign state; it could not conduct its own foreign policy distinct from that of the USSR, nor could it maintain a national army dedicated strictly to the defense of its own borders.

It is largely because of surviving without a sovereign nation state that Armenians have developed considerable “emotional patriotism.” Emotional patriotism flourishes with an idealized version of a lost or subjugated Fatherland and relates intimately to culture, language and faith, which sustain it. Operational patriotism, on the other hand, is tied to an existing sovereign state. The reality of an independent Armenian state is harsher than the idealized nostalgic Fatherland, and, as importantly, comes with an enormous responsibility; consequently, it has not been easy for emotional and operational patriotism to overlap.

A notable exception is the fighting soldiers and volunteers of the Armenian defense forces, for whom fighting to defend the “Fatherland” is a sacred mission, regardless of the “State” that sent them to war. Talking to dozens of military conscripts and officers since 2016, as well as family members of martyred soldiers and volunteers, I reached an overwhelming confirmation that their sense of duty was to fight for the Fatherland (Հայրենիք) and not necessarily for the prevailing government. Few parents, if any, would want their son to die defending the ruling elite, or the government, or even the abstract notion of Armenian Statehood. But most parents, and soldiers themselves, would sacrifice their lives defending what they call their “Hairenik.”

What’s the difference? International law defines a sovereign state as a political entity that has a permanent population, defined territory, one government and sovereignty, i.e., the capacity to enter into relations with other sovereign states. The concept of a “Hairenik,” on the other hand, needs only a cultural heritage, a population and a territory. The ideas of “government” and especially “sovereignty” have not always been part of the understanding of “Hairenik” and only marginally motivate the soldiers who would sacrifice their lives for it. Similarly, it was the notion of Hairenik that drove the people of Armenia to campaign for the unification of Artsakh with Armenia during Soviet times, when neither Armenia nor Artsakh had sovereign status. The Soviet Union could not extinguish the patriotism of Armenians, even often with the use of very brutal methods. That too was patriotism directed at a Hairenik, regardless of whether it was sovereign or not.1

What is evident among the soldiers is emotional patriotism crossing the line into operational patriotism when it comes to the physical defense of the Fatherland. Such crossovers are rare among the general population. They occur in the face of an external threat, but not as a matter of course. They almost never occur within the general government bureaucracy. If there is no threat to the Fatherland, strengthening the state apparatus, in and of itself, does not inspire or motivate the average citizen. In the past 30 years, the state apparatus has, more often than not, been a tool for personal gain rather than a supreme national end, a syndrome largely inherited from traditions formed in the Soviet era but rooted in the absence of a culture and tradition of sovereign statehood.

The distinction between emotional and operational patriotism is neither simple nor absolute. One of the paradoxes that I have struggled with over the past three decades is to observe a fundamentally patriotic population in Armenia who nonetheless does not hesitate to migrate at the first opportunity, who constantly re-elects the same oligarchs even while complaining about their corruption and nepotism, who does not hesitate to accept and offer bribes, and who uses as many of the loopholes in the system as he can, knowing very well that those loopholes are weakening the country that he loves. This seemingly contradictory behavior can be explained, at least in part, by the relatively insignificant role that the notion of statehood plays in emotional patriotism.

The lack of a sovereign-state tradition runs deep. It is one of the root causes of Armenia’s weakness today. Capitulation to a stronger military force comes naturally to those who are a product of this culture. Rather than seeing sovereignty as the foundation of national security, they see it as an impediment to national security, because sovereignty implies true independence with all the responsibilities that come with it, which is an alien and frightening concept for them and precludes the explicit protection of a larger power.

This mindset has reared its ugly head again in Armenia today, most notably through those who favor a unification with Russia and those who claim that Artsakh “was never ours.” That is the extreme manifestation of the mindset, but there are many shades of it, all characterized by a lack of faith in our own statehood.

The culture of statehood has two distinct, but interrelated sides: the conceptual/ideological side, whereby the importance of statehood manifests itself in the notion of self-governance and independence; and the governance side, the more practical aspects of running the state apparatus and governance. i.e., forming an effective government. One without the other is not only useless, but also dangerous. In Armenia, we have had one or the other in various periods since independence, but rarely both together.

It pains me to mention that what is going on in Armenia at present is further proof (and a consequence) of the lack of a culture of sovereign statehood. The quality of the political discourse, exemplified by an abundance of negatives with relatively few constructive ideas being aired (which get ignored), the alarming absence of accountability after the largest national losses of lives, territory and geopolitical position of the country since independence, the persistent arrogance of a defeated and blatantly incompetent administration, the refusal of the opposition groups to accept their share of the responsibility for the complacency, negligence and mistakes of the past 30 years which haunt the country to this day, the total disregard for the public’s right to know the details of what went wrong in the war, the failure of the National Assembly to put the national interest and the constitution above all other affiliations, the destructive conflict between the prime minister and the top leadership of the Armed Forces, the utter indifference of the entire political elite and the intellectual class to the destructive divisions in the country, are all testimony that saving the sovereignty of Armenia is, at best, only secondary in the minds of both the politicians and the public.

A major, nationwide paradigm shift is required to alter this psyche. But that will take time. We cannot afford to wait. It will also require a critical catalyst, which at present we do not have.

In the short-term, until a process of nationwide change is set in motion, damage control has to come from a well overdue new generation of leadership. This would be a group with an understanding and vision of statehood who can provide the Armenian public with a much-needed third political alternative. Obviously, such a group will not have experienced the tradition of statehood firsthand and will suffer from the same lack of experience in that sphere as the past political leadership. So, it needs to be a generation that has learned the most relevant lessons from our own history, as well as the history of other nations who have overcome similar handicaps. It needs to intrinsically understand the significance of nurturing a sovereign Armenian state. It needs to have unquestioned operational loyalty to the state, irrespective of political/party affiliation, and be fully and solely dedicated to the vision of a strong Armenian state. It needs to be composed of professionals, meritocrats, solution-oriented analysts, who can think outside the box. It needs to be a group of individuals who have managed their egos and are not after personal gain, power or fame. It needs to be a passionately nationalistic and at the same time worldly group, incorruptible, mission-oriented and ruthless in its pursuit.

Do enough people with these qualifications exist in Armenia and the Diaspora? I believe they do. The real challenge is that they come together, develop an articulate and coherent agenda, secure buy-in from the public and set an entirely new standard of governance and strategic thinking in Armenia. This needs to be done now. A group like this will not only manage the short-term damage control, but also act as the catalyst for the longer-term change in the national mindset.

As for the more fundamental long-term solution, it starts with the education system. Even after independence, the education establishment in Armenia did not recognize, let alone meet, the challenge of nurturing statehood, state security and citizenship in students. A major overhaul of the educational system is required.

At the outset, let’s recognize that the education system should be based on the simple principle that human creativity, unlike natural resources, never gets depleted or devalued. It is renewable, and much more than renewable, because it tends to not just renew itself, but multiply itself exponentially. It knows no limits. It achieves what conventional wisdom deems impossible. It surpasses its own assumed limitations. There is no stronger force in nature. Any educational system that fails to impart this notion to its student body, fails Armenia.

One key addition to the national curriculum at the elementary and high school levels should be courses in civics—rights and responsibilities of citizenship, the constitution and the rationale behind it, the nature and role of military service, branches of government and the logic behind them, the concept of accountability in public office, the role of the courts, examples of good and bad governance with the consequences of each for the state and the nation. We need to nurture citizens who are aware, beyond the hollow rhetoric of “proud” citizens of the past few years. National awareness, patriotism (beyond clichés), civic duties, culture of citizenship should start from childhood and grow and mature into adolescence.

The education system should be geared to address specific problems faced by a small country under constant military and often existential threat. A key requirement for the above, in addition to rigorous courses in all modern sciences and disciplines, is the proper teaching of Armenian history, which must go beyond its current emphasis on memorization of dates and events, and into historical and geopolitical lessons learned as they affected the Armenian state or as they prevented the creation of one. The present curriculum in schools in Armenia imparts no real sense of history to the students. In the past 30 years, I have made a habit of talking to schoolchildren of all ages in Armenia—in Yerevan as well as various villages in Vayots Dzor, Ashtarak and Aparan. What I observed was that the young people can generally recite dates, events and a few critical milestones in Armenian history, but they have been taught next to nothing about the significance of the history they have memorized, nor the overarching historical context within which the specific historical events that they cite have occurred.

The overhaul of the education system entails a fundamental paradigm shift in instruction and testing—away from standards and established systems of memorization. The dynamism, fluidity and creativity that Armenia should have in its economic and business model should be introduced in the education system. Established practices, standards and routines are deadly. Learning through experimentation, pushing the limits of the imagination, critical questioning and reasoning, improvisational skills (important both in military and civilian life), sense of mission, risk taking, are key. Quantitative stats alone—for example, number of schools, teacher/student ratios, etc., —are not indicative of quality of education. Quality and inventiveness of instruction methodology depend on how well the teachers understand their mission and how well they are trained.

The combination of the short-term catalytic trigger of a new generation of leaders with the fundamental overhaul of the education system could unleash a virtuous cycle of change in Armenia, which over time could spill into the culture, practice and legislation of civil service, thus transforming both the structure and modus operandi of the government. That would constitute a true revolution, because it would represent a change in the mindset of the nation. Only then will Armenia have a chance to finally uproot the post-Soviet oligarchic system and replace it with an effective, functioning state.

Otherwise, there is a good chance that we won’t be able to keep what we rebuild after the last war—even if we succeed to rebuild something worth keeping.

1Ironically, concern with the status of Artsakh has been an unintended contributing factor that diluted the significance of sovereignty among Armenians. To counter Azerbaijan’s legal claims on Karabakh, Armenian diplomacy systematically rejected any reference to territorial integrity and sovereignty in the international fora, instead of challenging the Soviet-era maps and rejecting Karabakh’s status as part of the internationally recognized borders of Azerbaijan. But this factor falls out of the scope of this article.