BY LUCINE KASBARIAN

“Soviet Armenian auteurs knew that to achieve prominence in the USSR in their fields of endeavor, the national dignity of the Armenian people would have to be sacrificed. That was the price to be paid.”

“Art is not what you see, but what you make others see.”

– Edgar Degas, French Impressionist artist

“Life imitates art far more than art imitates Life”

– Oscar Wilde, Irish playwright

“All art is political.”

– Lin-Manuel Miranda, Puerto Rican-American filmmaker

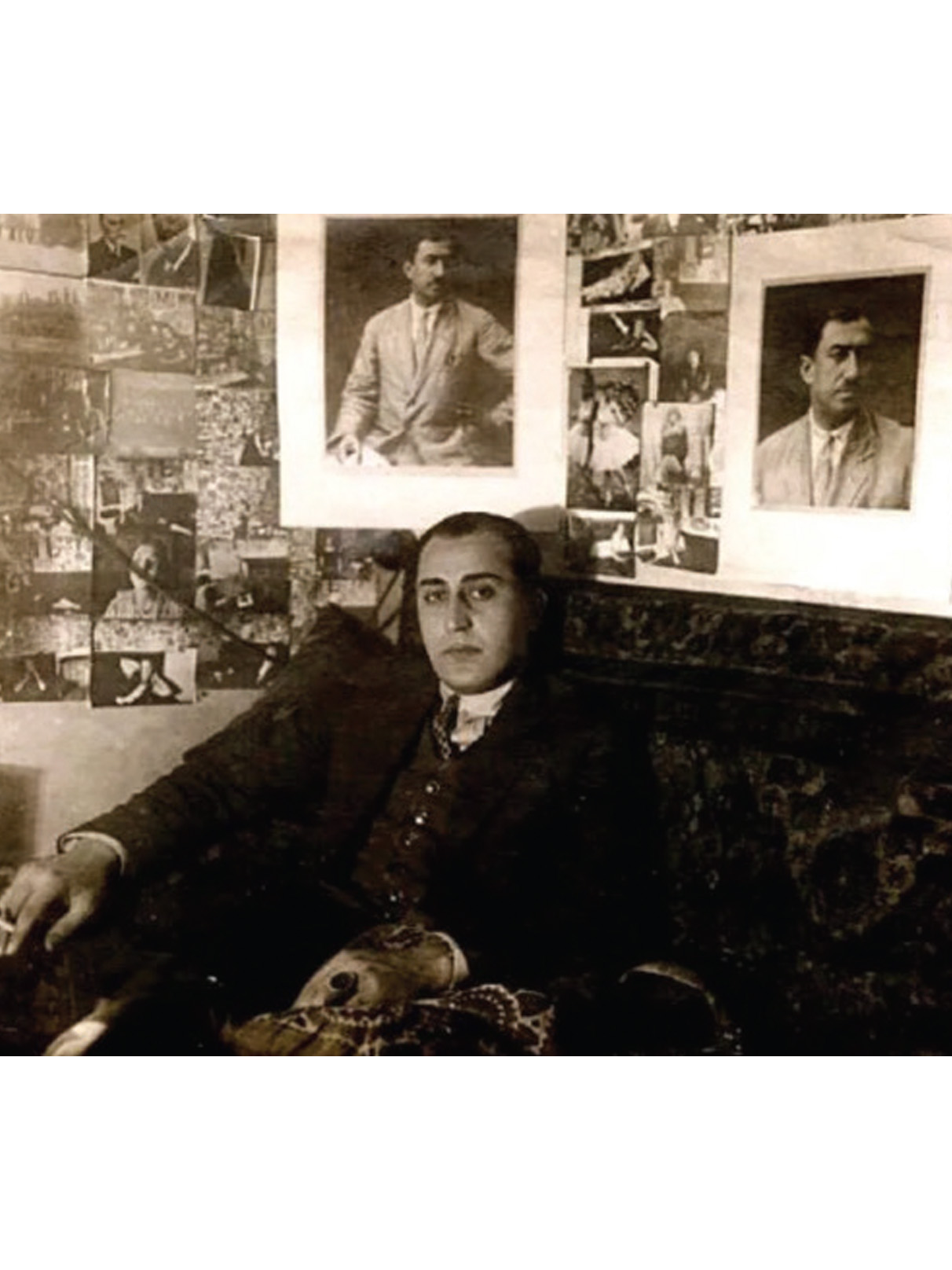

One can argue that all three quotations above apply to the two films screened at NYC’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in recent weeks. These films were “The House on the Volcano” (1928) and “Land of Nairi” (1930) directed by Hamo Bek-Nazaryan, widely considered the “founding father of Soviet Armenian cinema.” Both films were silent with Russian, Armenian and English intertitles and/or subtitles and accompanying music. Both contained staged material as well as actual documentary, location footage in Baku and Armenia. And both were recently restored in 4k format led by Vigen Galstyan, Founding Curator of Photography at the National Gallery of Armenia, digitally preserved by the National Cinema of Armenia. These recently restored films were screened as part of MoMA’s “To Save and Project” International Festival of Film Preservation.

Of the many films created by Bek-Nazaryan and other Armenian avant-garde film auteurs such as Ardavasd Peleshian, MoMA selected the above two films for its screening showcase. With the aid of a translator, Director of the National Cinema Center of Armenia Shushanik Mirzakhanyan—who was invited from Armenia by MoMA—addressed guests in the MoMA theater and expressed her thanks and that of Armenia’s Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport for the opportunity to introduce Bek-Nazaryan to a wider audience in the U.S. Other than this brief introduction, it is lamentable that there was no explanatory framework about the films provided to MoMA viewers nor a question & answer period after the films concluded. Both films, visually and dramatically arresting as they were, deserved some historical and ideological context for present-day viewers of any ethnic or social background.

From a storytelling standpoint, “A House on a Volcano” is a historical-melodrama-meets-disaster-film chronicling the lives and struggles of Armenian and Tatar oil refinery laborers and their Armenian bosses’ brutal suppression of an oil worker’s strike in pre-Soviet Baku (in what is present-day Azerbaijan). Just prior to the Communist Revolution, Baku was an imperial Russian territory hotly fought over by Ottoman Turks, Tatars, Jews, Germans, Brits, Americans, Russian Bolsheviks and Mensheviks as well as Armenian socialists, not to mention the Turkic, Jewish and Armenian oil magnates themselves, many of whom would later be ousted by the Soviets. The 7th-century Armenian philosopher, mathematician, geographer, astronomer and alchemist Anania Shirakatsi in his most famous work, “Geography” listed Alti-Bagavan (Baku) as one of the 12 districts of the Province Paytakaran (one of the 15 Provinces of the ancient Kingdom of Armenia). In the words of British General Lionel Dunsterville, “all understood that whomever controlled Baku controlled the Caspian Sea.”

The title of the film refers to the highly flammable gas leaks that circulated under the petroleum fields where the management knowingly and precariously built nearby housing for their laborers and families. In graphic detail, these seemingly dispensable workers were shown to be toiling 12 hour shifts a day under hazardous conditions. Russian writer of yore Maxim Gorky attested to the squalor and danger of the reservoirs when he, after visiting Baku, wrote, “The oil fields remained in my memory as a perfect picture of the grave hell.”

Even today, the level of environmental hazards and ruin in these oil fields are at an all-time high, with global elites irresponsibly rewarding top global polluter, rogue state, land grabber and human rights abuser Azerbaijan with hosting duties at the COP29 conference. The film plot, rife with Machiavellian machinations, creates an environment of accumulative intrigues which culminate in a crashing crescendo and chilling finale.

From a visual standpoint, “The House on a Volcano” is a stunning, gritty, mesmerizing art film one doesn’t soon forget. Even today, nearly 100 years after the film was produced, the close-up images of faces, places and machines remain arresting. Creative set designs, offset in black and white, are inventively employed using shading and light to accent scene compositions. The repetitive motions of industrial gears grinding and oil derrick pumps plunging into the black earth are in equal parts rhythmical, hypnotic and terrifying. The death-defying work undertaken by the laborers is frighteningly and effectively portrayed. According to restorer Galstyan, some movie sets were deliberately lit on fire for actors to run through and be filmed in real time. Viewing “The House on a Volcano” in the Millennium, one can recognize many manners of post-modernist industrial worker and labor union imagery the world later came to associate as uniquely Soviet.

From an ideological standpoint, the film is a Soviet propagandist’s dream come true. Bek-Nazaryan constructs a plot that plays out a specific vision of how racial and class divides are at the root of all evil. Alas, students of history know too well how the overthrowing of one predominant or exploitative group, class or race is often replaced by another, also quite true during the Communist Revolution. In a bid to mandate Soviet brotherhood over national unity, we see browbeaten Armenian and Tatar oil workers overcoming their ethnic differences and joining forces to overpower their malicious Armenian overlords—even when Armenian laborers are simultaneously suspected of being subversives who will serve their exploitative masters at the expense of their enslavement just to stick it to the Tatar-Azeris. Pun intended, the actors were almost uniformly striking (not just for going on strike) for their prominent ethnic physical features, frequently rough, coarse or ghoulish. The film’s visual interplay between light and dark often cast shadows on the player’s faces, giving them a dark tone, which served the widespread notion that there was a desire by the Soviets to pejoratively portray Armenians as the “negroes” of the soon-to-be Soviet Union.

What is telling is that during the early 20th century oil boom of Baku, there were many more Turkic and Jewish oil tycoons than Armenian ones. Even so, Bek-Nazaryan chose to make the villains in “The House on a Volcano” an Armenian oil baron and his cronies. Historically speaking, authors such as Suha Bolukbashi attest to the fact that it was, in fact, the Russian Imperial and Soviet leaderships who instigated tensions and distrust between Armenians and Azeris because they feared that nationalist movements among their ethnically non-Russian subjects would challenge Russian control over both.

Clearly it would have been beyond the scope of Bek-Nazaryan’s Soviet mandate to mention that the large and lively Armenian community of Baku was made up of intelligentsia, skilled professionals and craftsmen and or that 90% of the structures built in “the Paris of the Caucasus” at that time were by Armenian architects such as Hovhannes Khatchaznouni, Freidun Aghalyan, Vardan Sarkisov or Gabriel Ter-Mikayelov.

The Land of Nairi

The premise of “Land of Nairi” was to show the obstacles that Armenia had to face and overcome as it was altered from an independent republic to a Soviet state. Bek-Nazaryan used many of the same sorts of filmmaking techniques as he did in “The House on a Volcano”. Nairi being one of the ancient names for Armenia, the main character of this film was Armenia itself. Bek-Nazaryan created a number of raw, unrefined tableaus to demonstrate the challenges of rebuilding a nation and conspicuously steered clear of depicting the many glorious panoramas that characterize the Armenian homeland.

To illustrate a morally bankrupt aspect of capitalism, Bek-Nazaryan employed ham-handed concepts to depict how American relief aid to Armenians after WWI was both inadequate and patronizing. As flocks of peasants opened parcels from abroad, they discovered second-hand top hats and tails and beaded flapper dresses which were useless to the laborers as they donned these togs and tilled their fields in bitter exhaustion. The film offered no explanation for why Americans should assist Armenia, even though the rest of the world knew of the massive relief aid that was sent to support the cultural output of our own institutions aside, shouldn’t our own Armenian intellectual reservoirs—curators, educators and the like—be consulted or even hired? That would certainly be the case for other ethnic groups who demand and receive “representation.” As we return to identity politics, agency and self-representation by people of color in today’s progressive climate, will Armenians again be bypassed or will Armenian Lives Matter? As a long-time media and culture observer, I find the anti-Armenian trend in today’s high-profile literature, news media and the arts very hard to miss. It is not by accident.

In recent years, Azerbaijan has taken many hits for its massive contribution to environmental and industrial waste, pollution and even their outlawed use of white phosphorus – a poison on all living things — during their invasion of Armenian Artsakh. What better way to employ indirect lobbying for Azerbaijan and Turkey than for MoMA to showcase “The House on a Volcano,” which identifies Armenian oil magnates as environmental polluters and saboteurs?

As for the “Art is not what you see, but what you make others see” quotation, let us remember that the medium is the message and that Bek-Nazaryan like so many other visual storytellers and propagandists aimed for the messages to shape human behavior. Films are not simply art forms and storytelling venues. They are pedagogical tools.

As for the “Life imitates art far more than art imitates Life” quotation, one need only observe the anti-nationalistic policies undertaken by countless Soviet Armenian operatives and those in high office—all the way up to today. The behaviors and images seen on the silver screen did their part to erode patriotism from the map of the Armenian consciousness in some sectors and for which we today are still paying the price.

As for the “All Art is Political” quotation, why these movies and not restorations of the experimental films of Ardavast Peleshian such as “Seasons” or “We” which manage to be avant-garde artistically and simultaneously illustrative of the visceral soul of the Armenian people? And why at this particular time in history when Artsakh has been seized, when Azerbaijan, Turkey and Russia clamor